Open-source intelligence (OSINT) collection is a powerful means of keeping on top of threat actor activity, with representatives of the intelligence community estimating that approximately 80% of actionable intelligence is gathered from open sources. However, there are multiple problems in cyber intelligence collection, especially when it comes to OSINT, such as the challenge of data overload. These issues stress the overall necessity of a sound intelligence collection strategy, which ultimately helps inform the future stages of the intelligence cycle. This blog post will specifically focus on overlaps in activity attributed to Chinese advanced persistent threat (APT) actors in order to show how Silobreaker can be used to help simplify the process of OSINT data collection.

OSINT is particularly useful for monitoring Chinese APTs due to their activity often receiving widespread coverage. Chinese APTs frequently target government and critical infrastructure organisations, prompting government disclosures coordinated alongside research from various outlets, as was the case with the recent disruption of Flax Typhoon’s Raptor Train botnet. Chinese APT actors are also often referenced in the context of topics that are not always immediately related to cyberattacks, such as election interference and disinformation. This means information on Chinese APT activity is often abundant but heavily dispersed across differing types of sources.

Collecting actionable information on Chinese APT activity is also uniquely difficult due to how it has consistently evolved to become both stealthier and more complex to attribute. Chinese threat actors often rely on heavy use of living-off-the-land techniques paired with both commercial and open-source tools, as well as publicly available, fileless, or modular malware. Another factor complicating data collection is the frequent overlaps between different sets of Chinese threat actor activity, with security researcher BushidoToken noting that the recent leak of data from iSOON, a Chinese Ministry of Public Security contractor, entirely disrupted the idea of there being ’neatly defined threat groups conducting campaigns in a siloed manner’. Analysis of the iSOON leaks highlighted the significant level of overlap between different Chinese APT groups, demonstrating the potential and necessity of harnessing OSINT to identify further links. These overlaps assist with the overall processes of analysis and attribution, therefore making it easier to form effective countermeasures against Chinese APT activity.

Collecting data on recent Chinese APT activity

Through the usage of Silobreaker, multiple issues faced within the OSINT collection process can be immediately addressed, including the aforementioned challenge of information overload, as well as the necessity of source diversification and verifying the factuality and reliability of these sources. Of particular importance is ensuring parity between sources focused on both geopolitics and cybersecurity since, in the context of Chinese APTs, the two topics often intersect, as can be seen, for example, in TIDRONE’s reported targeting of military-related industries in Taiwan.

Using precompiled lists of trusted and verified data sources for varying topics, such as cybersecurity and geopolitics, as well as for more granular local reporting in different countries, assists the overall collection process and also helps reduce bias and ensure factuality in analytical outputs. For example, Silobreaker’s Analyst team also relies upon vetted lists to create their own reporting, which is designed to be accurate and relevant whilst eliminating the redundancy of mass collection.

Any dataset or list used can be queried easily to search for activity attributed to Chinese threat actors, made even easier by using Silobreaker’s curated and constantly updated list of China-linked actors. The same can be applied to distinguish between different threat actor typologies, such as APTs or hacktivist groups, offering the potential for more granular searches. For the purposes of this blog, however, only Chinese APT activity will be discussed.

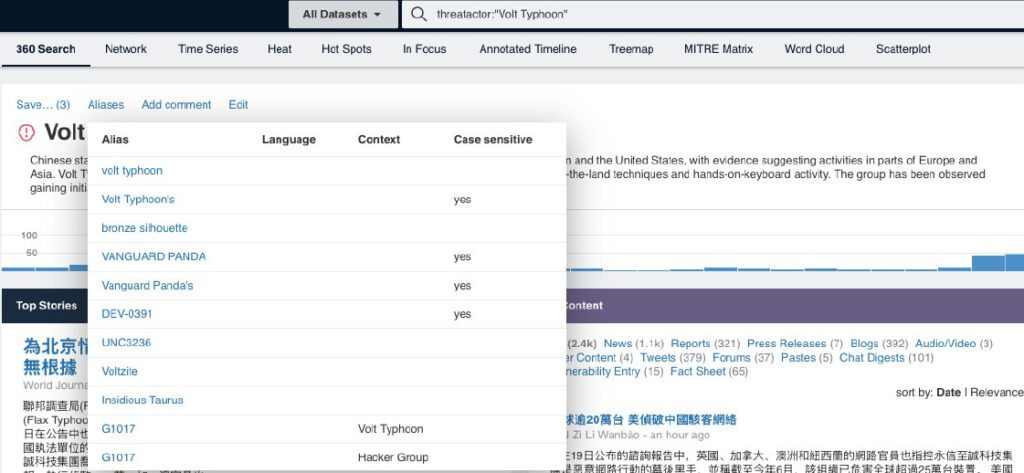

The aforementioned issue of attributing Chinese APT activity means that capturing all the monikers or ways an actor might be referred to is often very difficult. Multiple vendors and agencies might track the same or interlinked activity clusters by different names, meaning data collection needs to cover a vast and ever-changing set of monikers and nicknames – for example, APT41 activity is captured under various names, including Winnti, Barium, BlackFly, Wicked Panda, Starchy Taurus, TA415, and more. Entities within Silobreaker are constantly updated to account for threat actor names and how they might change, ensuring optimal coverage when it comes to intelligence gathering, as can be seen below.

Analysing OSINT Data – APT Activity

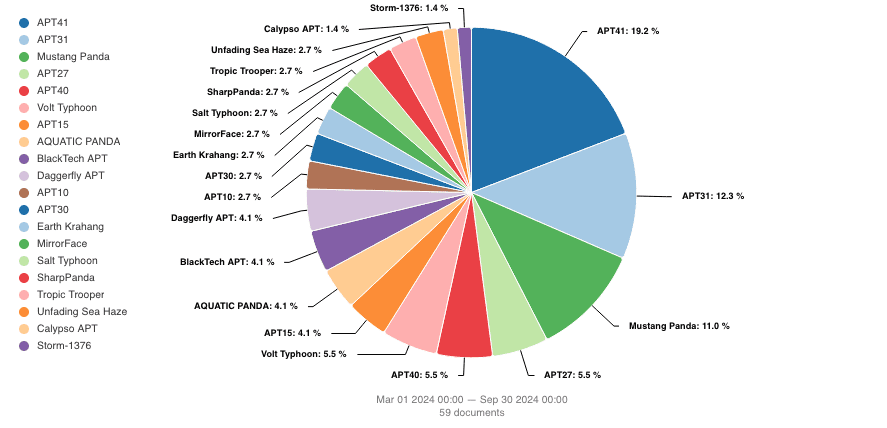

From information gathered and analysed throughout March 1st to September 30th, 2024, Chinese APT activity was most often attributed to APT41, APT31, and Mustang Panda. Notably, within the articles collected, there were also a number of cases involving multiple actors being linked to a single campaign, as was observed with Operation Diplomatic Specter and Operation Crimson Palace, both of which were also linked to APT41. This indicates the strong overlap between Chinese actors in terms of collaboration as well as the prevalence of sharing coding practices, tactics, techniques and procedures.

APT41 Activity

Throughout the analysed period, APT41 was most often observed targeting the government sector, followed by the research, shipping and logistics, media and entertainment, technology and automotive sectors.

One notable aspect of APT41-linked campaigns is that the threat actor is often conceptualised as an ‘umbrella group’ consisting of many separate activity clusters. Accordingly, some APT41-linked activity is attributed to suspected ‘sub-groups’, such as Earth Freybug, Earth Longzhi, Earth Baku and GroupCC. Research and attribution to APT41 therefore requires awareness of the unique tactics, targeting, and indicators of compromise associated with its particular sub-groups.

There are also multiple instances of threat activity that is not directly attributed to APT41, but still has some form of notable overlap with APT41 or one of its sub-groups. As mentioned before, both Operation Diplomatic Specter and Operation Crimson Palace were noted to have overlaps with APT41. In the case of Operation Crimson Palace, there were identified C2 infrastructure overlaps with the APT41 sub-group, Earth Longzhi. In Operation Diplomatic Specter, there were overlaps in operational infrastructure.

APT41 is also sometimes cited in examples of tools and code-sharing among Chinese threat actors. A recent campaign attributed to Unfading Sea Haze noted similarities between the delivered malware, SharpJSHandler and APT41’s funnyswitch backdoor.

APT31 Activity

Analysis of APT31-attributed activity indicated a few instances of overlap with other threat actors, most frequently APT27. Notably, APT31 was assessed to be collaborating with APT27 to target the Russian government and IT sectors as part of the EastWind campaign in August 2024. Trend Micro researchers also observed that, since 2020, Noodle RAT has been used by both APT31 and APT27, as well as Rocke Group and Calypso APT. Separately, Mandiant researchers noted that APT31 was one of multiple threat actors leveraging the FLORAHOX operational relay box network for cyber espionage operations.

APT31 was also frequently referenced in recent disclosures by the governments of the United States, New Zealand, Finland and the United Kingdom. The disclosures pertained to various APT31-attributed cyberattacks targeting the government, critical infrastructure and academic sectors.

As part of the US’ indictment of APT31-linked hackers, the hacker group was specifically attributed to China’s Hubei State Security Department. It was also alleged that, starting around 2010, APT31 began operating under the front company, Wuhan XRZ, with the group receiving additional support from another company named Wuhan Liuhe.

Mustang Panda Activity

Open-source reporting on Mustang Panda activity included campaigns targeting the government, education and shipping sectors. Mustang Panda’s custom NUPAKAGE malware, which is used for data exfiltration, was also observed being employed as a part of Operation Diplomatic Specter.

Multiple updates to Mustang Panda’s techniques and toolset were noted in the analysed period. This includes the propagation of PUBLOAD via a variant of HIUPAN worm, PUBLOAD being used to load additional tools, and a spear phishing campaign involving the DOWNBAIT and PULLBAIT downloaders. Starting September 2023, Mustang Panda was also observed using a new technique that involves the abuse of Visual Studio Code’s embedded reverse shell feature to execute arbitrary code and deliver additional payloads, including the ToneShell backdoor.

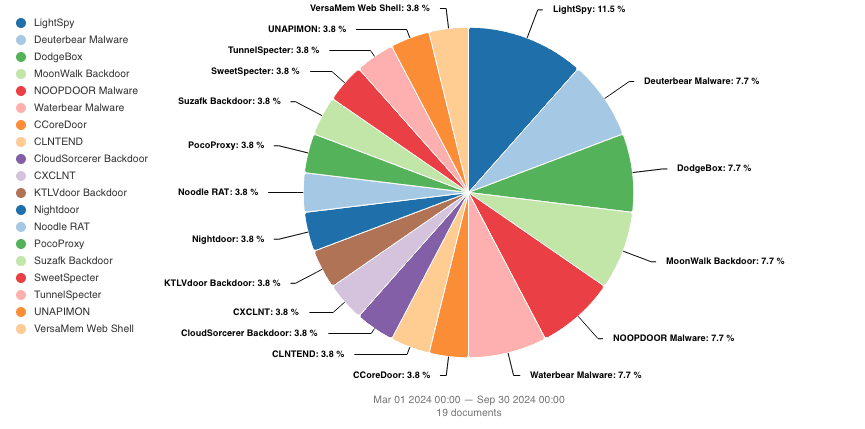

The collected data also helped collate a list of all new and updated China-linked malware that was observed in the research period. Of the new and updated malware, LightSpy was reported on the most, with other notable malware including DodgeBox, MoonWalk and both Deuterbear and Waterbear.

As previously mentioned, China-linked actors are known to leverage shared toolsets, meaning that the same malware can appear in multiple campaigns attributed to different actors. Notably, some malware, such as ShadowPad, is privately sold and deployed exclusively by multiple Chinese threat actors. Other malware that has been used across various China-linked campaigns by different threat actors includes China Chopper, PlugX, and its variants Korplug and DOPLUGS. This means that prior attribution of a malware’s usage to a specific threat actor does not necessarily apply in this case, as sharing of such malware appears to be abundant among Chinese threat actors.

LightSpy

A new LightSpy iteration, dubbed F_Warehouse, was reported on during the observed period. The malware was initially assumed to be an iOS implant, though Huntress researchers later determined that it is specifically designed to target macOS users. The variant has improved operational security and indicates more mature development practices. Previous research has attributed LightSpy to APT41.

The F_Warehouse variant was observed targeting individuals in Southern Asia and possibly India as part of an espionage campaign. Based on previous campaigns, the malware was likely delivered via compromised news websites carrying stories related to Hong Kong. ThreatFabric researchers subsequently identified LightSpy also being delivered via two publicly available exploits, tracked as CVE-2018-4233 and CVE-2018-4404.

DodgeBox and MoonWalk

DodgeBox is a reflective DLL loader that is believed to be an updated version of APT41’s StealthVector. DodgeBox was observed loading the MoonWalk backdoor, which uses Google Drive for C2 communications and abuses Windows Fibers to evade detection.

MoonWalk and DodgeBox share a common development kit, with both malware implementing various evasive techniques such as DLL hollowing, import resolution, DLL unhooking, and call stack spoofing. Both DodgeBox and MoonWalk are believed to be new additions to APT41’s toolkit.

DeuterBear and WaterBear

Trend Micro researchers identified a surge in BlackTech APT attacks employing Waterbear malware to target technology, research, and government organisations in the Asia Pacific region. A new iteration of Waterbear, dubbed Deuterbear, was also identified, which includes changes to anti-memory scanning and decryption routines.

Throughout the campaigns in which they were employed, updates to both Waterbear and Deuterbear were observed. Deuterbear’s new features include the ability to accept plugins with shellcode formats, as well as being able to function without handshakes during remote access trojan operations. The evolution of both malware indicates the continued development of tools for anti-analysis and detection evasion in BlackTech APT’s toolbox.

Conclusion

This blog post illustrates how OSINT can be leveraged to monitor updates to the toolsets and tactics employed by China-linked APTs, giving greater insights into the different kind of threats posed by such groups. Silobreaker can also be leveraged to simplify this process and address some key challenges in intelligence collection, particularly those that are unique to China-linked APT activity. If you would like to learn more about how Silobreaker can help your organisation in its OSINT collection efforts, please get in touch here.