The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted an almost unprecedented resurgence of hacktivist activities, following years of sporadic activity. As both cyber and physical attacks ensued, a spawn of hacktivist groups on both sides of the conflict emerged.

Hacktivism is a complex phenomenon in which religious or political beliefs fuel cyberattacks, as actors attempt to advance their causes through technology and digital disruption. It is a branch of cyberattack that uses a variety of techniques, depending on the resources available to the hackers. These techniques are continually evolving as new technologies become increasingly accessible.

The new wave of hacktivism that emerged during the war, which is not restricted to the likes of Russia and Ukraine, comes with new tactics, approaches and sophistication, often increasingly blurring the lines between hacktivism and government-sponsored attacks.

Ukraine IT Army

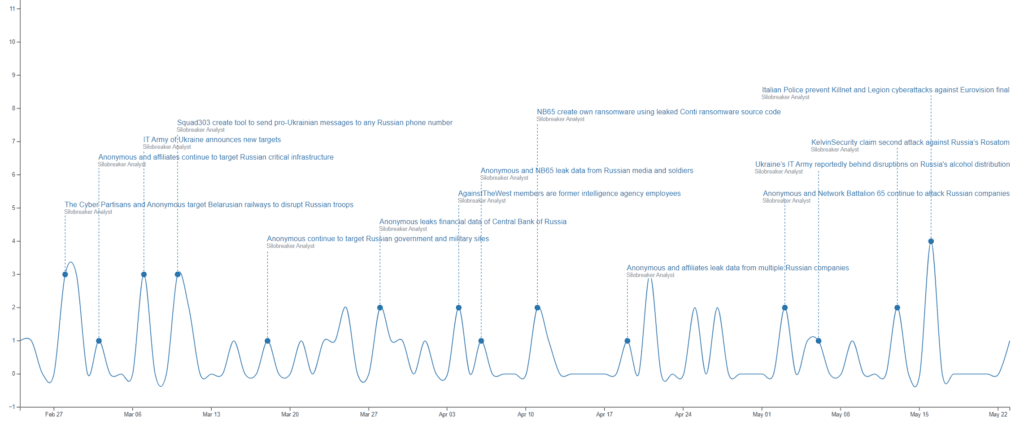

The optimal example of this is the Ukraine IT Army, a volunteer group of hackers from around the world that emerged following an initiative by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence at the start of the war. The IT Army was recruited to assist in cyberattacks against Russia and protect the interests of Ukraine in cyberspace, gaining over 186,000 members on its Telegram channel in a little over a year.

The IT Army has since contributed to distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) and hack and leak attacks against various organisations, joined by factions of Anonymous, under the #OpRussia tag. The group’s alleged victims include, but are not limited to, the Russian state-controlled companies Gazprom, VTB Bank and Sberbank, transportation links in Belarus and Russia and various government agencies. Ukraine’s government is now seeking to legalise the hacker collective by attempting to bring it into its armed forces division.

Other pro-Ukraine hacktivist groups, including the Cyber Partisans, AgainstTheWest and NB65, have also contributed to attacks on Russian or Belarusian infrastructure and organisations, resulting in hundreds of gigabytes of data being published online.

Pro-Russia Hacktivism

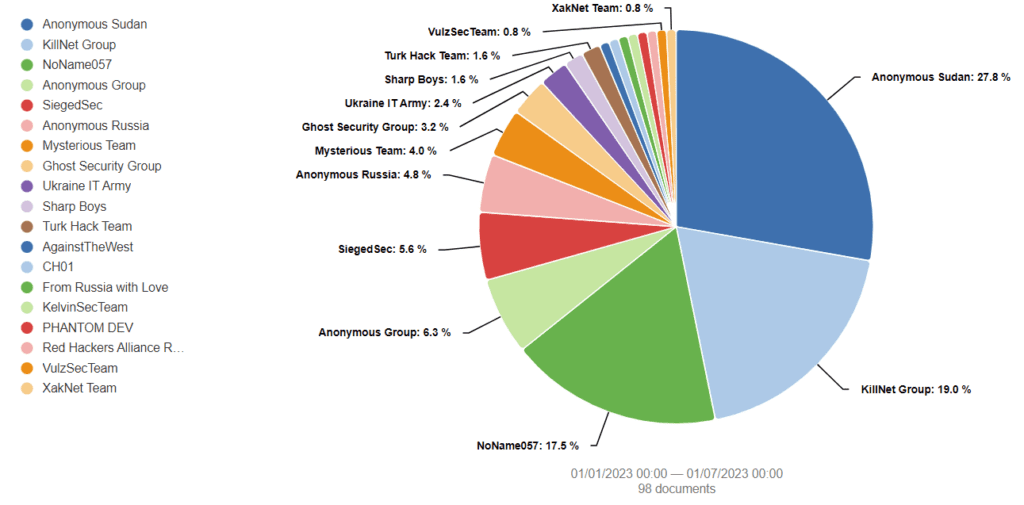

On the other side of the conflict, pro-Russia hacktivist groups have been no less busy, with several high-profile groups emerging at the start of the war, including NoName057, From Russia with Love, XakNet and KillNet. These groups, which primarily engage in DDoS attacks, have targeted critical infrastructure, media, energy and government entities, trying their best to cause high-scale disruption.

Figure 1: Timeline of select hacktivist activity from Silobreaker reporting between 24th February and 24th May 2022

These pro-Russia groups have also expanded the scope of attack beyond the borders of Russia and Ukraine. Western and NATO nations supporting Ukraine have found themselves at the mercy of these hacking groups, with hospitals, governments, banks and other critical sectors across Europe having been victimised. Countries such as Sweden and Finland have been targeted in protest of their possible NATO accession, and recently, NoName targeted New Zealand in retaliation for its sanctions against Russia.

KillNet

One of the most prominent pro-Russian groups to have emerged is KillNet, which arguably represents a new, very interesting breed of hacktivist group. Having formed in late 2021, the group is perhaps best known for its provocative nature rather than its attack capabilities. KillNet is spearheaded by its leader, KillMilk, who garners support for his crowdsource collective from other self-proclaimed hacktivists. In recent months, KillNet has announced both its intention to transform into a private military hacking company, dubbed BlackSkills, and the creation of a ‘Darknet Parliament’ alongside the heads of Anonymous Sudan and the notorious REvil. In June 2023, the group claimed it would be disbanding, before KillMilk announced he would be running the operation alone. The group continued to announce targets throughout the month, including the European Investment Bank and the International Finance Corporation, before going quiet in July 2023.

Anonymous Sudan

Despite KillNet’s prolific nature, it was not in fact the most active hacktivist group in the first half of 2023. This honour belongs to Anonymous Sudan, which emerged in January 2023 and quickly made consistent headlines. Anonymous Sudan claims to be composed of politically motivated hackers from Sudan, who have continually cited incidents such as Quran burning as motivations for attacks. To date, the actors have targeted a broad range of sectors, including critical infrastructure, financial services, government and more, across Europe, Australia, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Iran and the United States. The group even successfully targeted Microsoft in June 2023.

However, speculations about this group’s origins and motivations have troubled security researchers. Despite appearing to parade around as part of the Anonymous collective, Truesec researchers debunked this claim in February by determining that this iteration of Anonymous Sudan had no links to the original one, which was established in 2019 in response to ongoing political and economic challenges in the country. The researchers instead believe that the group was likely created as part of a Russian information operation to harm and complicate Sweden’s NATO application.

Other researchers have come to similar conclusions, with CyberCX researchers also assessing that Anonymous Sudan is possibly affiliated with the Russian state. Radware, however, has countered these conclusions, pointing out that the group operates in the Sudan time zone, demonstrates impeccable Arabic and targets countries whose policies are detrimental to Sudan rather than Russia. In fact, so far this year the group joined the #OpAustralia campaign alongside pro-Islamic hacktivists after an Australian fashion label featured models wearing designs with ‘Allah walks with me’ inscribed in Arabic across them and claimed to have successfully targeted the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces.

This ultimately leaves us with the question of who Anonymous Sudan really is. Are they in fact a pro-Russian influence operation, or Sudanese hacktivists? Most likely, there are two groups with this name that coexist, operating similar campaigns for different causes.

The Rest of the World

Hacktivist activities have also been on the rise outside the boundaries of the Russia-Ukraine war, as actors continue to respond to changing political issues and societal conflicts occurring worldwide.

In the first half of 2023, multiple distinct campaigns have been launched against India by groups like Team_insane_pk, Mysterious Team Bangladesh, Eagle Cyber Crew, Ganosec Team, VulzSec and more, with several of the campaigns being joined by numerous other hacktivist groups. The attackers have cited the treatment of Indian Muslims as the cause for these attacks, as well as retaliation for attacks conducted by Indian sympathetic hacktivists. In response, groups such as Anonymous India, Indian Cyber Force and Kerala Cyber Extractors have launched coordinated waves of attacks on organisations from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Pakistan.

The SiegedSec hacker group has targeted numerous state-run websites, satellite systems and cities in the United States in response to multiple states banning gender-affirming care. Guacamaya has conducted multiple hack and leak campaigns against military and police agencies and mining companies across Latin America, which they believe have played a role in the region’s environmental degradation and repression of native populations. Religiously driven campaigns have been conducted against Israel, India and Australia, and political campaigns against Poland, the United States, Germany and France.

Figure 2: Hacktivist mentions in Silobreaker reporting in H1 2023

Conclusion

The surge of hacktivism that has accompanied the Russia-Ukraine war has changed the dynamics of traditional warfare, setting a precedent for any future wars to be fought on both physical and cyber fronts. Hacktivist activity is likely to continue to increase, and it’s not just the governments and entities involved in warfare that are at risk. As some of the examples from across the world have shown, any political or societal issue can influence hacktivist activity, meaning any organisation, regardless of industry or size, has the potential to become a target of hacktivism. For this reason, it has become essential for organisations to monitor cyber threats from specific actors, while also keeping up-to-date with any ongoing geopolitical situations that may influence these threats.

To learn about some of the knock-on effects of the war in Ukraine, including the impact on sanctions, affected sectors, the cyber threat landscape and Russia-China relations, sign up to receive our Russia-Ukraine Insights Alert directly to your inbox here.